In antiquity crucifixion was considered one of the most brutal and shameful modes of death. Probably originating with the Assyrians and Babylonians, it was used systematically by the Persians in the 6th century BC. Alexander the Great brought it from there to the eastern Mediterranean countries in the 4th century BC, and the Phoenicians introduced it to Rome in the 3rd century BC. It was virtually never used in pre-Hellenic Greece. The Romans perfected crucifion for 500 years until it was abolished by Constantine I in the 4th century AD. Crucifixion in Roman times was applied mostly to slaves, disgraced soldiers, Christians and foreigners–only very rarely to Roman citizens. Death, usually after 6 hours–4 days, was due to multifactorial pathology: after-effects of compulsory scourging and maiming, haemorrhage and dehydration causing hypovolaemic shock and pain, but the most important factor was progressive asphyxia caused by impairment of respiratory movement. Resultant anoxaemia exaggerated hypovolaemic shock. Death was probably commonly precipitated by cardiac arrest, caused by vasovagal reflexes, initiated inter alia by severe anoxaemia, severe pain, body blows and breaking of the large bones. The attending Roman guards could only leave the site after the victim had died, and were known to precipitate death by means of deliberate fracturing of the tibia and/or fibula, spear stab wounds into the heart, sharp blows to the front of the chest, or a smoking fire built at the foot of the cross to asphyxiate the victim.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14750495/

Crucifixion was generally performed within Ancient Rome as a means to dissuade others from perpetrating similar crimes, with victims sometimes left on display after death as a warning. Crucifixion was intended to provide a death that was particularly slow, painful (hence the term excruciating, literally “out of crucifying”), gruesome, humiliating, and public, using whatever means were most expedient for that goal.Crucifixion was intended to be a gruesome spectacle: the most painful and humiliating death imaginable.[86][87] It was used to punish slaves, pirates, and enemies of the state. It was originally reserved for slaves (hence still called “supplicium servile” by Seneca), and later extended to citizens of the lower classes (humiliores).[31] The victims of crucifixion were stripped naked[31][88] and put on public display[89][90] while they were slowly tortured to death so that they would serve as a spectacle and an example.

Crucifixion was such a gruesome and humiliating way to die that the subject was somewhat of a taboo in Roman culture, and few crucifixions were specifically documented.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crucifixion

Crucifixion most likely began with the Assyrians and Babylonians, and it was also practiced systematically by the Persians in the sixth century B.C., according to a 2003 report in the South African Medical Journal (SAMJ). At this time, the victims were usually tied, feet dangling, to a tree or post; crosses weren’t used until Roman times, according to the report.From there, Alexander the Great, who invaded Persia as he built his empire, brought the practice to eastern Mediterranean countries in the fourth century B.C. But Roman officials weren’t aware of the practice until they encountered it while fighting Carthage during the Punic Wars in the third century B.C.

For the next 500 years, the Romans “perfected crucifixion” until Constantine I abolished it in the fourth century A.D., co-authors Francois Retief and Louise Cilliers, professors in the Department of English and Classical Culture at the University of the Free State in South Africa, wrote in the SAMJ report.

However, given that crucifixion was seen as an extremely shameful way to die, Rome tended not to crucify its own citizens. Instead, slaves, disgraced soldiers, Christians, foreigners, and — in particular — political activists often lost their lives in this way, Retief and Cilliers reported.

The practice became especially popular in the Roman-occupied Holy Land. In 4 B.C., the Roman general Varus crucified 2,000 Jews, and there were mass crucifixions during the first century A.D., according to the Roman-Jewish historian Josephus. “Christ was crucified on the pretext that he instigated rebellion against Rome, on a par with zealots and other political activists,” the authors wrote in the report.

https://www.livescience.com/65283-cruci … story.html

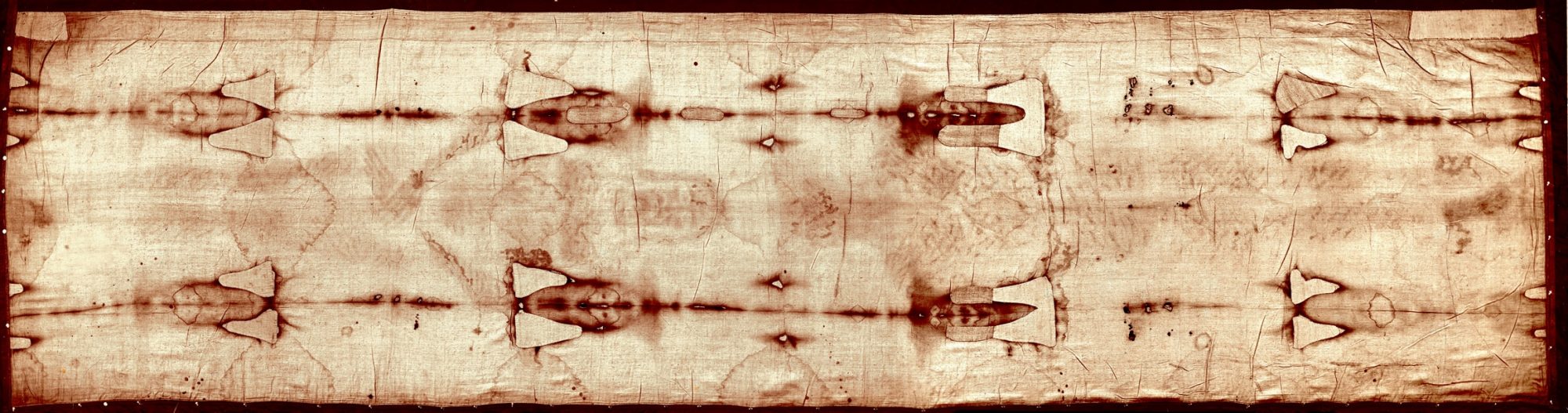

It’s accepted by both authenticists and skeptics the TS depicts a man that has been crucified.

From the medical aspect, the Shroud of Turin shows a badly battered

body with numerous areas of traumatic injury; apparent, swelling and

bruising of the face; numerous areas showing evidence of scourging

probably with a two-thonged scourge; and wounds consistent with a

crucifixion of a man who died on the cross and was buried in a linen shroud

which completely covered the body, both front and back.

https://epublications.marquette.edu/cgi … ontext=lnq

Pope Benedict XVI, called it an “icon written with the blood of a whipped man, crowned with thorns, crucified and pierced on his right side”.Pope Francis referred to it as an “icon of a man scourged and crucified”.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shroud_of_Turin

“Even if the shroud was authentically proven to come from 1st century Judea, this would only show that someone was crucified”

https://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Shroud_of_Turin

Outside of the Bible and the TS, we actually have very little textual records or archaeological evidence for us to know the details about crucifixion, in particular how victims were nailed to the cross.

“The literary sources for the Roman period contain numerous descriptions of crucifixion but few exact details as to how the condemned were affixed to the cross.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jehohanan

“Little historical information is available about the means of crucifixion in the Roman period”

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/a … 8314005245

It was in 1968 that an artifact was discovered of a crucified person from the 1st century.

Although the Roman historians Josephus and Appian refer to the crucifixion of thousands of Jews by the Romans, there are few actual archaeological remains. An exception is the crucified body of a Jew dating back to the first century CE which was discovered at Givat HaMivtar, Jerusalem in 1968.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Crucifixion

Jehohanan (Yehohanan) was a man put to death by crucifixion in the 1st century CE, whose ossuary was found in 1968 when building contractors working in Giv’at ha-Mivtar, a Jewish neighborhood in northern East Jerusalem, accidentally uncovered a Jewish tomb.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jehohanan

We are not even sure how often victims were nailed or tied to the cross in antiquity.

This near total absence of any direct anthropological evidence for crucifixion in antiquity bears the question of why, aside from the case described above, is the record silent.

There are two possibilities which may account for this silence, one is that most victims may have been tied to the cross. In Christian art, the Good and the Bad thieves are depicted as being tied to the cross despite the fact that the Gospels do not go into detail as to how they were affixed to the cross. Scholars have in fact argued that crucifixion was a bloodless form of death because the victims were tied to the cross.

https://web.archive.org/web/20070302091 … xion2.html

There are some possible reasons why we have so little archaeological artifacts of crucified victims:

– Wooden crosses don’t survive, as they degraded long ago or were re-used.– Victims of crucifixion were usually criminals and therefore not formally buried, just exposed or thrown into a river or trash heap. It’s difficult to identify these bodies, and scavenging animals would have done further damage to the bones.

– Crucifixion nails were believed to have magical or medicinal properties, so they were often taken from a victim. Without a nail in place, it becomes more difficult to tell crucifixion from animal scavengers’ puncture marks.

– For the most part, crucifixion involved soft tissue injuries that can’t be seen on bone. Only if a person had nails driven through his bones or was subject to crurifragium would there be significant bony evidence of the practice.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinaki … f5f382476d

If crucifixions were common, one would expect to find more than just one crucifixion artifact in the history of archeaology.

Since the Romans crucified people from at least the 3rd century BC until the emperor Constantine banned the practice in 337 AD out of respect for Jesus and the cross’s potent symbolism for Christianity, it would follow that archaeological evidence of crucifixion would have been found all over the Empire . And yet only one bioarchaeological example of crucifixion has ever been found.The bioarchaeology of crucifixion is therefore a bit of a conundrum: it makes sense that finding evidence may be difficult because of the ravages of time on bones and wooden crosses, but the sheer volume of people killed in this way over centuries should have given us more direct evidence of the practice.

https://www.forbes.com/sites/kristinaki … f5f382476d

Bart Ehrman posits one possible reason is it was the standard procedure for crucified victims in antiquity to rot on the cross and then thrown into a pit.

And so Romans did not allow crucified victims – especially enemies of the state – to be buried. They left them on the crosses as their bodies rot and the scavengers went on the attack. To allow a decent burial was to cave into the desires precisely of the people who were being mocked and taught a lesson. No decency allowed. The body has to rot, and then we toss it into a grave.

https://ehrmanblog.org/why-romans-crucified-people/

So what is remarkable is that the TS gives us greater understanding of ancient crucifixion, in particular now we know nails had to go through the wrist, instead of the palms as all medieval art had portrayed it. How would a medieval artist know about how crucifixion should be done? We have no records of how crucifixions were precisely done by the Romans. And we only have one artifact of a crucified person — and that was only a foot. How could a forger have had access to written records of how crucifixions were actually done or access to archaeological remains of a nail through the wrist when we know so little?

Further, if Ehrman is correct and it was the common practice to have Roman crucifixion victims rot and thrown into a pit, then it would make the man on the TS even more likely to be Jesus Christ, since very few, if any, would’ve been allowed a quick burial.

https://debatingchristianity.com/forum/viewtopic.php?p=1108120#p1108120